Where Are The Levers In The Pleasure Garden

The commercial pleasure garden was not a Victorian invention. Vauxhall Gardens in Lambeth possessed a lineage dating back to the 1660s, when John Evelyn described the New Spring Garden at Fox-Hall as "a pretty contrived plantation." By the mid-eighteenth century, the landscaped garden contained assorted decorative additions: "pavilions, lodges, groves, grottos…temples and cascades; porticos, colonnades, and rotundas…pillars, statues, and paintings." Trade was seasonal, restricted to the summer months, and the garden was open from early evening to the small hours. Visitors came to promenade, dine, and listen to music outdoors. Rival gardens, large and small, peppered the fringes of the Georgian metropolis. Pleasure gardens were always situated in this liminal position, their lawns, shrubberies, and arbors offering a carefully curated rusticity. Larger venues, like Vauxhall, operated as independent enterprises; smaller gardens were usually adjuncts to taverns. Some grounds also opened by day: Marylebone Gardens, although popular by night, offered breakfast with "tea, coffee, cream, butter, etc." and "no improper company." The original attraction of Bagnigge Wells in Islington was its supposedly medicinal mineral waters. There were also simple "tea-gardens" which offered afternoon tea or a pleasant supper.

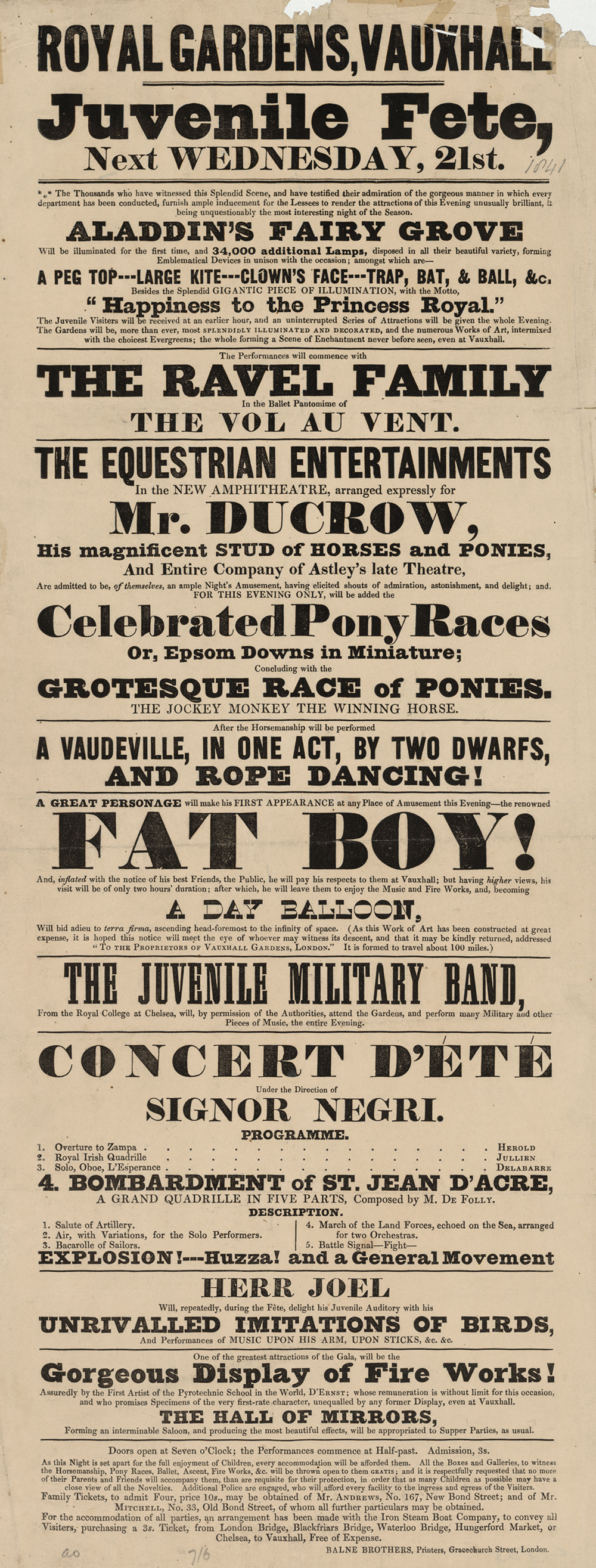

What exactly went on in the commercial pleasure garden, beyond drinking and dining? It is quite difficult to describe "typical" pleasure-garden entertainments. The multifarious amusements differed not only from place to place but from year to year. Novelty was very important. Managers of larger gardens could spend several thousand pounds each year not only hiring new entertainers but constructing entire new buildings: a different style of theater, a new dancing platform a more elaborate architectural folly. The press dutifully reported on these extensive alterations and improvements, and hopefully the public attended with renewed curiosity.

Vauxhall Gardens provides us with a useful initial benchmark. Indeed, such was its fame and longevity that "Vauxhall" was often used as a straightforward synonym for "pleasure garden": several other towns and cities—including New York—boasted their own "Vauxhall Gardens," named after the original. If we take the 1820s as our starting point, visitors could arrive by road or via the Thames. The ground's location in South London was still relatively rural, although the bricks and mortar of the metropolis were beginning to encroach, helped by the opening of Vauxhall Bridge in 1816, which had created a convenient transport link to the West End. Vauxhall Gardens itself was an enclosed, cultivated park. The public came to saunter along its graveled paths, down tree-lined avenues, lit by innumerable colored oil lamps; or along canvas-covered cast-iron colonnades. One end of the gardens featured a "dark walk" for those who required romantic privacy, but the overall impression was one of astonishing brightness and brilliance. The lights numbered in their thousands, and their sheer profusion more than compensated for the lack of modern, brighter gaslight. One might come upon various talking points while taking a stroll: twin grand triumphal arches, a transparent portrait of George IV, a scene painting of a "submarine cavern" with a real waterfall, the "Heptaplasiesoptron" (a set of seven mirrors reflecting "revolving pillars and palm trees, twining serpents and a fountain of real water…lighted by colored lamps"). Throughout the site, paintings, panoramas, and "cosmoramas," which included three-dimensional effects and lighting, produced a magical, otherworldly feel. Many visitors, however, chose to inhabit the alcove-like supper-boxes along principal avenues, where groups could sit, dine, and drink.

The key location in the grounds for actual entertainment was the "orchestra," an elaborate two-story gothic bandstand with a built-in organ. Musicians and singers performed from the open upper tier to rapt crowds. In bad weather, the music was adjourned to the gardens' circular rotunda assembly room ("an Indian garden-room, the prevailing colors of which—scarlet, blue, and yellow—are most effectively shewn by a sumptuous cut-glass chandelier"). Other buildings in the 1820s included a theater where comedies and ballets were performed; an ornate platform for launching firework displays; a ballroom attached to the Rotunda; a "hermitage" where one could have one's fortune told by the solitary inhabitant; and a gallery containing paintings on patriotic/military themes, along with a seemingly transparent "magic clock." Visitors could pick and choose from these diverse amusements. Concerts, both indoors and outdoors, were supplemented by variety acts: Ramo Samee, the famed Indian juggler; Mr. Blackmore (stage name "The America"), who performed nightly on the tight and slack rope while wearing a cap fitted with fireworks; Ching Lau Lauro, the acrobat and contortionist; Signor Spelterini, "The Wonderful Italian Hercules"; and, in 1830, the peculiarly popular performance of Michael Boai, "whose unrivaled music on his chin has drawn forth such great astonishment and delight." Large open-air spectacles in the late 1820s included a firework-packed re-creation of the Battle of Waterloo and Cooke's Equestrian Circus (both were first seen at Astley's Amphitheatre, a popular venue for equestrian and circus shows, located nearby). One novel exhibition re-created James Clark Ross' expedition to the North Pole, replete with a ship entombed in faux icebergs, "which are as large as reality, many being upwards of seventy feet high…seen floating on the waves…the whole Area of Ground appears as one entire moving mass of ice." Ross' icebergs were not only elaborate and expensive to stage, but topical—the polar expedition was still very much in the public consciousness. This was, therefore, a particularly unique and extravagant display, since it could not be profitably repeated the following season.

To a degree, the pleasure garden was a vacant space that could be filled with virtually any form of spectacle or popular amusement. The most common pleasure-garden spectacle was undoubtedly the firework display, rounding off the evening with a literal bang. Such displays dated back to the mid-eighteenth century and would remain a staple throughout the Victorian period. Pyrotechnics could also be incorporated into other performances, whether as a backdrop to circus acts performed outdoors, especially tightrope walkers, or during theatrical set pieces that made use of the extensive grounds, such as dramatic re-creations of famous battles. Patriotic themes for displays were always popular. During the 1850s, Cremorne Gardens in Chelsea staged its own explosive tributes to British troops fighting in both the Crimean War and the Indian Mutiny. Similarly, Manchester's Belle Vue and Pomona Gardens each had its own rival diorama of the Siege of Sebastopol, with nightly pyrotechnics restaging the onslaught. Surrey Gardens in Walworth, on a less militaristic note, employed pyrotechnic and lighting effects to present the nightly eruption of Mount Vesuvius. Oriental settings were also popular, with the "firing of the Golden Temple of Honan" playing for two seasons at Vauxhall, then transferring to Manchester. Some pyrotechnicians were more radical in their choice of subject matter. Joseph Gyngell (aka "Signor Gellini"), based at Rosherville Gardens in Gravesend, put on "pyrotechnic ballets," which combined lights and fireworks with live performance. The 1855 season featured "The Freaks of Will o' the Wisp," a highly topical allegory on cleanliness and public health in the age of cholera, with "imps" representing individual epidemic diseases, vanquished by "Hygeia," the spirit of health.

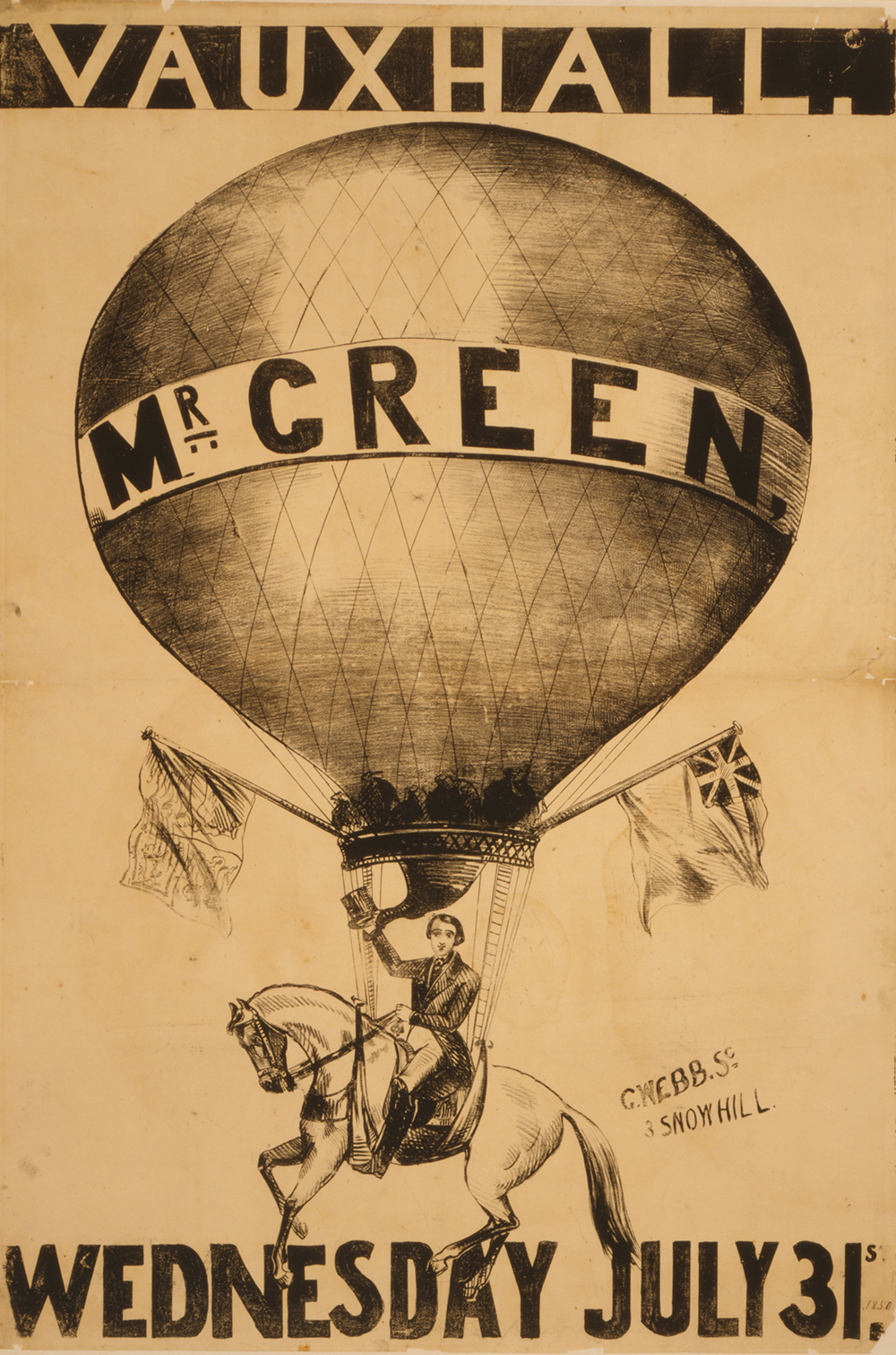

The other great spectacle was the "balloon ascent," popular ever since the Montgolfiers' first flight in 1783. Intrepid aeronauts launched themselves into the ether, accompanied by music and cheered on by a crowd of paying visitors. Vauxhall Gardens actually has its own peculiar place in the early history of aviation. The balloonist Charles Green set a long-distance flight record in the Royal Vauxhall Balloon, travelling from Lambeth to the Duchy of Nassau in Germany in 1836. His vehicle was promptly renamed the Great Nassau, and made further flights from Vauxhall and other gardens, drawing huge audiences. Balloon ascents were usually much-publicized special occasions rather than a nightly occurrence, but they were a great crowd-pleaser. Thomas Rouse, when establishing the Eagle Tavern in Islington in the 1820s, made sure to include ballooning in the pleasure garden's initial attractions. Rouse charged a shilling for entrance, which allowed a closer view of the balloon and its elaborate "car," decorated with crimson velvet, festooned with fringes of deep green and yellow silk. A further shilling secured access to an "inner ring" or stand, close to the launch site; and gentlemen occasionally paid a hefty premium to actually go along for the ride. The danger of ballooning was palpable, and the audience at the Eagle gasped when one aeronaut, named Harris, took along a volunteer from the crowd, one Miss Stocks, a mere thirteen-year-old girl, on an ascent in May 1824. Their fears were not unfounded: Mr. Harris crashed the balloon in Carshalton, losing his life. Miss Stocks (who later turned out to be an eighteen-year-old out-of-work pastry cook "of a romantic turn of mind") went on to become something of a minor celebrity. The popularity of Rouse's balloon displays was such that surging crowds, unwilling or unable to pay a shilling, repeatedly blocked neighboring roads and thronged adjoining rooftops. On one occasion, a makeshift scaffold erected on slum cottages behind the ground collapsed, leaving four people dead and several dozen spectators injured.

Aeronauts also took up nonhuman companions. Monkeys and cats were released from airborne balloons, dispatched from the heavens in their own miniature "cars" with parachutes. This was supposedly a scientific experiment, but it conveniently also "afforded great amusement to the children." Charles Green and others regularly ejected "Signor Jacopo, the Celebrated Monkey" from balloons at Surrey Gardens and Vauxhall. Local residents kept a careful watch on the skies, since an attached label promised the finder £2 and free admission to the Surrey Zoological Gardens. Some aeronauts took things a stage further: horses (and other quadrupeds) were tethered under the balloon, to be lifted into the air. A certain Madame Poitevin ascended from Cremorne Gardens on the back of a bull, depicting "Europa and the Bull." The balloon landed in Ilford, east of London, and the animal subsequently died of exhaustion and fright.

However, during the Victorian period, public sentiment grew more hostile to blatant exploitation of animals. The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals successfully prosecuted Madame Poitevin and her husband, who was piloting the balloon. Cremorne Gardens' owner, T.B. Simpson, disingenuously blamed the animal's terrified demise on rowdy, unsophisticated locals who surrounded the fallen creature, remarking that a bull plummeting from the sky was "a thing not seen every day in Essex." Frequenters of pleasure gardens could also enjoy the antics of occasional (human) parachutists, pilots of makeshift gliders and assorted "flying machines." Fatalities among the inventors of flying machines were predictably high. Vincent de Groof, for example, took off from Cremorne Gardens in 1874, tethered to a balloon in his winged "machine," manufactured from cane and silk, with wings operated by levers. He had supposedly successfully piloted the device on a previous voyage on the Continent, reportedly "flying" to earth from a height of a thousand feet. Unfortunately, on this occasion, whether by accident or design, he detached from the balloon at a mere eighty feet. He was found dead, with multiple injuries, in the churchyard of St. Luke's parish church, Chelsea.

Other dangerous acts could also take advantage of an outdoor space. Signor Sebastiano Botturi walked through a burning shed in a fireproof suit that resembled "a Polar Bear on its hind legs," with "two glass eyes, or rather windows, which glared without speculation on the company." The Times reviewed Botturi rather harshly: "he shed was much too small, and the stay of the Signor within it much too short."

There were also considerably tamer circus performers and variety acts. Favorites at Cremorne were the "Beckwith Frogs," the family of Fred Beckwith, a champion swimmer. They appeared underwater in a specially made glass tank, performing such mundane tasks as "smoking" a pipe or "eating" breakfast.

Adapted from Palaces of Pleasure: From Music Halls to the Seaside to Football, How the Victorians Invented Mass Entertainment, by Lee Jackson, just published by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2019 Yale University Press. Reprinted by permission of Yale University Press.

Where Are The Levers In The Pleasure Garden

Source: https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/roundtable/may-we-entertain-you

Posted by: jacksonbabinfor.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Where Are The Levers In The Pleasure Garden"

Post a Comment